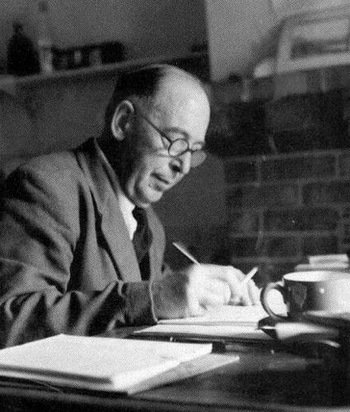

Last evening, a dear friend of mine invited me to read C.S. Lewis’ essay, “The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment” in which Lewis offers a criticism of legal theories that prioritize rehabilitation and/or deterrence over notions of just deserts. What I found both surprised and disappointed in light of Lewis’ other writings and his admiration for thinkers like Geo rge MacDonald, whom Lewis refers to as his master.

rge MacDonald, whom Lewis refers to as his master.

Given Lewis’ status in the Christian world, mere attempts at criticism risk being dismissed as hubris. Nevertheless, I see in Lewis’ argument an erroneous predisposition that has long plagued not only Western civil law but also Western Christianity, and thus merits a response.

Lewis’ central claim is that, despite their benevolent intentions, advocates of humanitarian punishment undermine the relevant authority’s grounds for determining just deserts: “… take away desert and the whole morality of the punishment disappears. Why, in Heaven’s name, am I to be sacrificed to the good of society in this way? – unless, of course, I deserve it.”

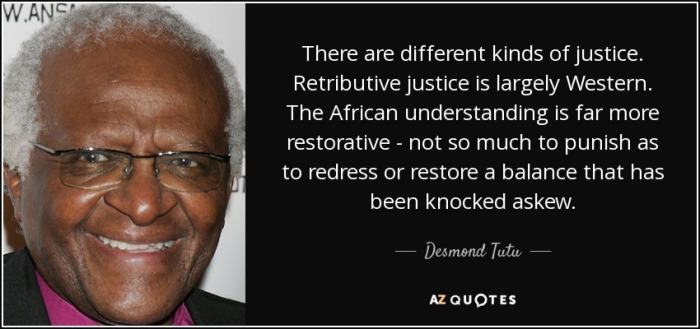

Those who, like Lewis, have been conditioned within the Western European legal paradigm may take as granted the claim that certain actions demand a retributive response. They may even recognize a certain logic in Lewis’ argument. But it is in taking retributive justice for granted and failing to substantiate his presuppositions that Lewis’ argument fails.

Matters of law, justice and ethics in general must necessarily begin with the end, or purpose, in view because ends provide the only coherent basis for grounding and guiding legal and ethical determinations in specific cases. For instance, a utilitarian society will hold that its primary goal is a society that maximizes the well-being of the greatest number of people and its laws and judgments will be enforced in light of this end. If a prospective judgment results in an unnecessary decrease in the overall well-being of the society it can be dismissed as harmful and unnecessary within this utilitarian framework.

Lewis is unclear as to the primary end that law and justice should serve in society. He upholds the importance of retribution and just deserts for the sake of morality and human rights but provides little to substantiate his argument. This begs two questions: 1) What end, if any, does retributive justice serve? 2) Is this end superior to alternatives? Put differently, we should ask if it is even proper to begin from notions of just deserts.

What is the purpose of legal retribution? Does it solve the problem it seeks to address? If a murderer is executed for killing another person many would declare that justice has been done and perhaps even that the problem has been solved. Seeing a perpetrator punished might give some satisfaction to those bereaved, but this is not restitution. But killing the killer doesn’t bring the victim back to life. One might instead argue that killing murderers communicates a deterring message to the society at large. However, reducing justice to a deterrent is rejected by Lewis because, according to him, it has nothing to do with what the criminal deserves for his crime.

Let’s take a less extreme example. Suppose a thief is charged for stealing $100. Restitution would be achieved by simply returning the money to its rightful owner and perhaps making amends for any damages or hardships that resulted from this theft. One might even argue that an additional fine or punishment is required to deter future theft. Again, though, this would fall under the humanitarian, deterrent forms of punishment Lewis rejects. He maintains that some sort of retributive punishment is required for the sake of justice, apart from deterrence and restitution.

This takes us back to question 1 – What end does retributive justice – in and of itself, apart from restitution and deterrence – serve? One searches in vain for a persuasive answer because retribution appears to have no purpose other than conforming to an unsubstantiated notion of just deserts.

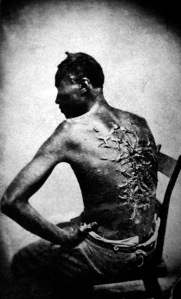

The closest Lewis comes to substantiating his notion of just deserts relates to his appeal to human rights. Society should have a say in determining what constitutes a just punishment, which upholds the will of the people. For any serious student of history, this is a frightening prospect. The masses have often demanded or at least condoned “just” punishments that we now see as abhorrent. Lutherans and Calvinists tortured and massacred Anabaptists for believing differently than they did. The United States built itself up through legal slavery for nearly a century. Fourteen-year-old George Stinney was wrongfully executed by the State of South Carolina, sentenced without due process by a jury of his peers. All three examples were seen as just.

demanded or at least condoned “just” punishments that we now see as abhorrent. Lutherans and Calvinists tortured and massacred Anabaptists for believing differently than they did. The United States built itself up through legal slavery for nearly a century. Fourteen-year-old George Stinney was wrongfully executed by the State of South Carolina, sentenced without due process by a jury of his peers. All three examples were seen as just.

Perhaps Lewis would appeal to his understanding of Divine Law. God is the ultimate law giver and has decreed that His justice demands retribution. The problems with this approach are, first, it isn’t mentioned in Lewis’ article and second, can be understood in a number of ways, as has been the case throughout the history of Christianity. Furthermore, the ultimate punishment one can suffer in Lewis’ theological framework, eternal damnation from God, results not from God’s retributive act but from the free choice of those damned.

Some Christians viewed punishment as a means to an end similar to advocates of Humanitarian Punishment Theory while others saw punishment as an end in itself. Biblical and theological arguments are made for both perspectives. Nevertheless, if Lewis wishes to uphold punishment on the basis of just deserts the question remains – what good does it accomplish to punish someone simply because they deserve it?

Thus the second question – Is this end, being retribution for the sake of just deserts, superior to alternative approaches? Does it offer more explanatory power or persuasive force? Clearly not, and I would go as far as saying that the very theory that Lewis criticizes offers a much more persuasive account of the ends punishment should serve. The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment outlines several potential and positive ends for punishment, including remediation, restitution and deterrence. A criminal’s sentence can work for their own good, providing them resources for becoming a law-abiding member of society, and for the good of society, protecting citizens from being further victimized by the criminal. As stated previously, punishing criminals acts as a deterrent to society at large by showing citizens what happens to perpetrators. However, punishment for the sake of retribution alone is merely a cruel and frivolous response that provides no solution to the problem it seeks to address.

Furthermore, evidence reveals the numerous benefits of a remedial approach over a retributive:

In Norway, the incarceration rate is about 75/100,000 people, and the recidivism rate is the lowest in the world at around 20 percent. In the US, more than 700/100,000 people are incarcerated, and more than 70 percent of freed inmates are re-arrested within five years.What is the difference between the two systems? Although America’s system says it’s about rehabilitation, its actions focus on punishment and confinement. Norway walks the walk and talks the talk when it comes to rehabilitation and restorative justice, and considers a loss of freedom punishment enough. The focus is on helping inmates prepare to re-enter society with the people and job skills they need.

Perhaps Lewis would have stuck to the wisdom of his master:

“God is not bound to punish sin; he is bound to destroy sin.

The only vengeance worth having on sin

is to make the sinner himself its executioner.”

― George MacDonald